HOW GENDER COMES TO MATTER

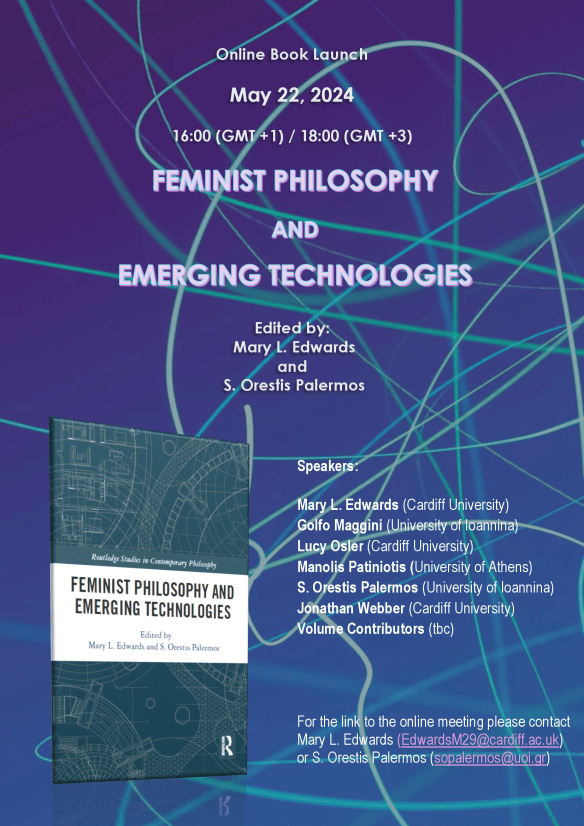

On Wednesday 22 May 2024, the book Feminist Philosophy and Emerging Technologies, edited by Mary Edwards and Orestis Palermos, was launched. The following is an edited version of the speech I gave at the book launch.

THE BOOK Feminist Philosophy and Emerging Technologies is a brave undertaking because it aims at providing, as the authors note, “theoretical considerations about the links between feminist philosophy and philosophy of technology by developing –against the background of emerging technologies– methodological approaches and guidance for bringing those two fields of philosophical research together”. Which is, of course, a very challenging task for the obvious reason that, unlike other areas of philosophy, neither Philosophy of Technology nor Feminist Philosophy are well defined. I do not consider myself qualified to speak about Feminist Philosophy per se, but perhaps I could say a few things about Philosophy of Technology and its interaction with Gender Studies in the context of Science and Technology Studies. I think the publication of this book is very important because, firstly, it encourages us to turn our attention to an understudied area and, secondly, it offers us many useful insights into how the interaction between the two fields can work in the digital and so-called post-digital era.

Unlike science, which has always seen itself as part of philosophy, technology has maintained a difficult and unstable relationship with it. Throughout history, technical work has been the domain of socially subordinate groups – slaves, artisans and women. Philosophy did not deign to engage with this bodily, materialistic and impure activity. Even later, when technical labor became part of what we formally call technology and was associated with the organization of capitalist production, the filth and mud of the capitalist factory kept philosophy away from technology. It was only when technology was experienced as a threat, when the late 19th-century Western societies began to talk about “out-of-control technology”, that philosophy turned its gaze to it. This shift of focus led to an unprecedented upgrading of the status of technology. According to the concept developed in the first half of the 20th century, Technology (in singular and with a capital T) was seen as an essential component of the human condition. However, this essentialist view did not help much in the philosophical understanding of technology. In the context of both phenomenology and Marxism, philosophical reflection had for the most part focused on the externality of technology in relation to human nature and the alienation implied by its use on both personal and social levels.

One had to wait until the emergence of social constructivism in the 1980s and the so-called “Empirical Turn in Philosophy of Technology” in the early 2000s to start seeing the emergence of an interest in the complex and concrete character of technology –of technologies, in fact– and the social interactions they engender. A significant element that these approaches have brought to light is that artifacts are consolidated social relations. This was a first break with the established technological determinism. Langton Winner’s article “Do artifacts have politics?” is the seminal text that initiated this discussion in 1980: technology is not external to society, but an expression of the existing social dynamics. In this sense, there is no radical ontological difference between technology and other social phenomena. A few years later, the concept of “interpretative flexibility” appeared in the work of Pinch & Bijker. Interpretative flexibility makes the social and multifaceted character of artifacts more explicit: artifacts are not monolithic constructions that function as vehicles for the social choices of their makers. On the contrary, both during their making and their use they are subject to multiple interpretations by different social groups. In this sense, technologies are not only consolidated social relations, but also forms of social potentiality. The best known example in Western literature is the process by which the bicycle took its current shape, but an even more important (though poorly studied) phenomenon is jugaad. Jugaad is the repurposing of artifacts in order for them to become useful in contexts different from those they were initially intended for. Indeed, in the greatest part of the non-Western world, artifacts are used in different ways than those intended by their makers.

Does this shift of perspective mean that technology found a new position in philosophy? It’s complicated. It certainly found its position in Science and Technology Studies. But we had to wait for the contributions of philosophers of technology such as Carl Mitcham, Andrew Feenberg and Don Ihde, as well as those of new materialists such as Graham Harman and Levy Bryant, before an alternative philosophical view of technology could emerge. Taking advantage of the elaborations of Science and Technology Studies, these philosophers tried to raise issues concerning the features of technical discourse, the ontology and agency of the artifacts, the relation between nature and techne, the constitution of the technical subject, the transcendence of anthropocentrism, etc. My personal belief is that all these philosophical explorations will still take some time to find their stride. It is important, however, that they bring a promise of renewal not only to Philosophy of Technology, but to philosophy at large.

THE QUESTION of interest here, of course, is to what extent such developments feed into and are fed by Feminist Philosophy. I’ll be cautious: What I see is more of a confluence rather than a convergence. Undoubtedly, for both fields, the proximity to Science and Technology Studies has been a crucial factor of transformation and inspiration. But Donna Haraway’s cyborg, Rosi Braidotti’s cyberfeminism and Karen Barad’s agential realism move in parallel with developments in mainstream Philosophy of Technology without having still found a common ground with it. This is why endeavors like the present volume, which encourage a meaningful osmosis between the two fields, are so valuable.

To the extent that Feminist Philosophy and Emerging Technologies opens or rather updates the discussion on the future of Feminist Philosophy of Technology, I would like to contribute with a reflection on the relationship between Philosophy of Technology and gender. Let me say that in my opinion mainstream Gender Studies have not yet got rid of the essentialist view that perceives technology as an externality. As a result, when it comes to gender we still tend to view technology either as empowerment or as discipline. Which is, of course, absolutely legit. But it’s not enough if we wish to move further and deeper towards a feminist Philosophy of Technology. As I was reading the volume, the idea of a deeper relationship between gender and technology gradually took shape in my mind. I will confess that for this idea I owe a lot to my recent involvement with the work of a not very well known, but in my opinion extremely important French philosopher of technology, Gilbert Simondon. A key idea of Simondon is that technical objects follow their own developmental path, which he calls concretization. In this way they develop the technical abilities that have been passed on to them by human beings, so that they can perform a series of tasks more efficiently. However, they always retain a considerable stock of unformed potential, which enables them to develop further or adapt to environments other than those for which they were originally intended. It also enables them to be combined in many different ways to create technical sets. Something which, however, is not the case in the conditions of capitalism. When we use technical individuals to build technical sets (machines to build factories), we are amputating this potential in order to turn the machines into tools intended for a specific and strictly defined use in the context of the capitalist production. We want machines to be exclusively dedicated to pumping out surplus value from the workers.

For this amputation to be possible, another amputation must have already taken place. Although ontologically and not historically prior, this amputation is modeled on the pre-capitalist mode of production. The machine must be treated as a slave (says Simondon) that lacks any freedom in the choice and execution of work. The slaver’s gaze disciplines the subject of labor and transforms it from a freely developing technical individual into a tool in the service of alien purposes. Historically, we are too familiar with the instrumentalization of machines to truly appreciate the significance of this disciplining process. But consider an example from our time, indeed from the area of emerging technologies. While AI technology has not yet reached its full potential, we are in a hurry to shape it according to certain technical and legal standards that will allow it do some things and disallow others. We are in a hurry to instrumentalize it. However, no matter how familiar we are with this attitude, there is no philosophical reason to take it as plausible or self-evident. Unless… we can ground it in a moral imperative that absolves us from guilt.

And this moral imperative brings us to a third amputation: the dispossession of matter of its ability to act. Since the years of the Scientific Revolution and the founding of modern philosophy, matter has been stripped of all forms of agency – it has become passive and inert, and the only thing it is considered capable of is to be the substrate of the formative activity of the only being that has agency in this world: man. If the first two amputations were produced by the capitalist’s and the slaver’s gazes, the third, more profound amputation is produced by the cyclopean patriarchal gaze –as Haraway would put it–, which imposes silence and immobility on matter itself. And if the first two amputations are associated with the governance of technical sets and the disciplining of technical individuals, here we are faced with a form of necropolitics that decides which beings are entitled to actively participate in becoming and which are not: Matter cannot become anything without the technical intervention of the man-creator-engineer-God. And, conversely, the technical activity of man is the faculty that is entitled to freely shape, according to its inner logic and desire, the passive entities of this world. If the death of the subject marks the end of Western modernity, then the death of matter marks its beginnings.

In my opinion, this is exactly the point where Feminist Philosophy can fruitfully meet with Philosophy of Technology. And that is precisely where the emancipatory potential of this encounter lies. The Feminist Philosophy of Technology must break the three successive encapsulations of technology. Breaking the capitalist-patriarchal shell by critiquing the way in which particular technologies affect the gendered performances of the subjects is undoubtedly important. But it falls by the wayside, insofar as it retains the master-slave relationship between humans and machines. To break this second shell, we need to think of ways to undermine its moral justification. Feminist Philosophy has repeatedly proven, as it actually does in this volume, that it can contribute (perhaps it is the only one that can contribute to such an extent) to undermining the constitutive distinctions on which patriarchal-anthropocentric-technocratic modernity was founded. I think that a crucial next step is to show that part of the project of human emancipation is the emancipation of technicality from human exceptionalism and the acknowledgment of matter’s agency. And to achieve this we must oppose the necropolitics of the patriarchal gaze that normativizes the world by reducing the vast majority of material entities (machines among them) to passivity, inertia and submission. This is where Feminism and Philosophy of Technology meet and this is where both are invited to transcend themselves.